Two

years ago I retired from teaching. My

original Social Security card lays in the left side drawer of my writing

desk. The ballpoint ink of my signature

as a fifteen-year-old is still blue. My signature has matured, but I

can remember signing the card.

Officially,

I’d been a college professor for 26 years.

Before that I worked as a grad school teaching assistant and an English

instructor in Poland. I worked in libraries, bookstores, and nursery

schools. Along the way odd part-time

gigs kept me going---serving as a Shabbos goy in a private home, an office

assistant for an auctioneer, typing bills of lading in a shipping office out on

a pier in San Francisco.

More

than forty years of work life passed in the blink of an eye, as the cliché

goes. I

was stunned when I reached “my full benefit age”---that foundational concept of

the Social Security Administration.

What

hit me hard was how little life was left to do anything else. Twenty-five years remained if I matched my

mother’s life span. She lived to 91. Fewer years if I lived as long as her mother, my

grandmother, who lived to 88. I call

them my hardy matrilineals. Less time left than the “blink of an eye” I’d just lived through.

Time

to go. Now.

Unfinished

goals that still nagged me---a second promotion, a monograph in my field---what

did they matter now? More money, more points plotted along an academic career graph. Did I want to spend my only years of life left

on them?

I re-focused fast.

I re-focused fast.

Since

then I’ve settled into what we call retirement. I’ve pondered the language. In Jane

Austen novels it meant to withdraw from social life, to live in seclusion. Or to be diffident and quiet. As in, “she’s a very retiring person,” or she

lives in the country “in retirement.”

When

Germany pioneered modern social insurance for workers in 1889, we got the

notion of retirement from paid work. Historian

Richard Gabryszewski narrates a video about the development of social insurance

behind our Social Security system. You

can find it on the SSA website. It’s a noble story and I love it. I’m proud to be a part of a history that (if

we skip the workhouse era) includes Aristotle, olive oil, Frances Perkins, and FDR.

Thanks

to them all, my monthly social security benefit slips silently into my checking

account. I have time to write, to cook

and to garden, to read. Few dates recur in

my calendar---yoga classes, the dentist, the financial planner, and the

doctor. There’s time to understand point

and figure charts, to practice long form tai chi.

All

in all, my transition has been successful.

My daily life habits are comfortable. As I say, I have settled in. Or so I thought.

One

day last year, making the bed and gazing absently out the unwashed windows of my

now mortgage-free house, a surprising thought surfaced from my subconscious. It flickered,

illumined, and then slipped below again.

The

thought is hard to re-capture, but the gist is this. So much of the advice elders dinned into my once

youthful and compliant head seems irrelevant now. Family expectations and exhortations (and the views

and values they rested on) aimed at girding me for

the precarious path to a future successful adult life.

My

elders worried, I suppose, that I might not make it to this point. Their worry has long since been laid to rest.

What remains of their counsel has transformed completely, or just fallen to the

side, shards of another era. I made it. Here I am.

Except that I’m someone else.

Why

would this thought emerge now?

I

think it has to do with the irony of retirement, maybe its paradox, or even its subtext, as the literary say.

This

is pretty heavy. I’m writing an essay to try to figure it out.

My

parents and grandparents were well-meaning and I don’t fault them. They wanted happiness and security for me. They

survived the Depression and World War II.

We

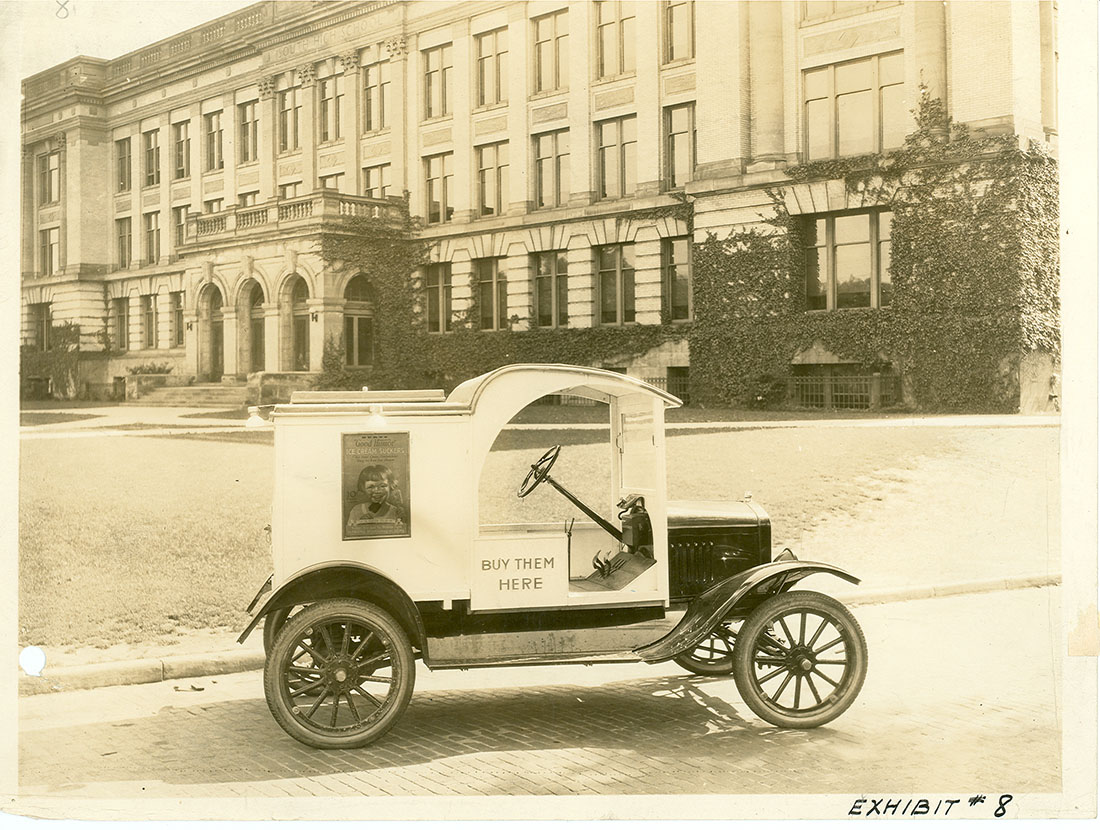

lived together, three generations. They told their stories around our dinner table: a job lost in New York City and pushing a Good

Humor ice cream cart, dismissal from college because of debt, surviving in the

Pacific during the war, a paralyzing stroke and no medical insurance, having to

sell the family store and move in with relatives.

I was the only child and much beloved, listening at that table. I absorbed these family tales. Accounts of disaster seemed normal to me. My elders’ history was so real to me that growing up I thought everyone had these same stories.

My

parents had scrambled on to the widening ledge of 1950s prosperity. Their expectations for me centered on college,

the education that history could snatch away at any time. By 1959 I was on the march in my blue blazer,

plaid skirt, and the Spaulding shoes of my Catholic high school uniform. College meant the liberal arts---English and

history, Latin and the classics, modern languages. Fields like sociology so

popular among my girlfriends were beneath consideration. (If I’d had any aptitude for math or sciences

things might have been different.)

Other

family expectations remained hazy: a good marriage, dignified work (no real professional

career), travel, maybe some artistic or creative pursuit. By my senior year in college, I suspected

that---unlike belief in education---these expectations were shaped by social convention. With

no immediate prospects of attaining any of them, and graduation imminent, I

began to question my life.

I embarked on my belated rebellion.

I embarked on my belated rebellion.

It

wasn’t hard. The upheavals of the 1960s spurred me on. I’d missed civil rights---a bit too young. One

day my English lit professor stopped his lecture to explain Mario Savio and the

Free Speech Movement. I went to anti-war

rallies and sat in at sit ins. Women’s issues burbled below the politics.

I

sleepwalked through some of the counterculture’s colorful enthusiasms---pot and

music. Concerts at the Fillmore

auditorium conveniently combined both. The movement

years waned. Institutions I’d been

raised with papered over their gaps and fissures, and hobbled on. I graduated from

college but was never the same.

I wrestled

with mistakes of judgment (a difficult marriage). But the education thing perdured---a

word that age and time teaches you to love. In

midlife I plunged into grad school and completed a PhD. Through dogged

determination and fortuitous circumstances, I got a faculty post, and then tenure.

I supported myself, raised my son, cared for my aging mother, and paid off a

house.

Academe

became my home, the source of meaning and a livelihood. I hung onto it tightly,

clutched it as sure and worthy.

When

I retired, friends asked about my plans. They chirped excitedly about travel

and volunteering---eager to offer ways

to fill time once hogged by gainful employment. Bring satisfaction and value to

retirement, people said. Give back, do more, keep active.

That’s

where the irony came in. Other people’s

enthusiasm was unnerving. After decades of

marching through education, work and profession, this pressing you to do

something else disconcerted me.

I panicked. Untethered from a job would I drift into

dissatisfaction and depression? Had I misjudged the whole 25-year rest of life

thing?

It

took a year to accept this irony of retirement---that no one wants you to

withdraw into quietness at all. I’ve

pretty much let that go. My time obsession

has shifted into its sister dimension. It’s

become more like space left to me---open and uncluttered, airy and

agnostic. I am learning to feel free, perhaps for the first time since adolescence. I can explore again, without the anxious anticipation

of adulthood.

And

there’s some work only I can do---understand how people and experiences changed

me. I ruminate about my elders’ ideas

of a successful life, chiseled in hardship and the demands of inherited social

convention. Maybe this is why the notion

of their expectations surfaced in my mind.

It illumined something---that I’ve long been someone else. It’s a paradox of retirement that now I can

love my elders again, though their advice seems antique and their wisdom has

transformed or just fallen away.

If

there’s any subtext to retirement (a risky proposition), maybe it’s something structural. If another phase of retired life follows this

one, I won’t be surprised. But for now it’s time to get on with this inward

journey.

In

dreams and in my mind’s eye I see those elders who drilled their exhortations

and expectations into my young self. Now

I have the ridged nails, the crinkly skin, and the sinking chest of my hardy

matrilineals. I wish they had told me more about their lives then, lives of

middle age and old age, though I wouldn’t have understood. But it’s alright. I talk to them again.

I’m the last of those around my family dinner table.

Read more essays like this one in East Village Magazine at http://www.eastvillagemagazine.org/en/

I’m the last of those around my family dinner table.

Read more essays like this one in East Village Magazine at http://www.eastvillagemagazine.org/en/

No comments:

Post a Comment